Why is English not more like German?

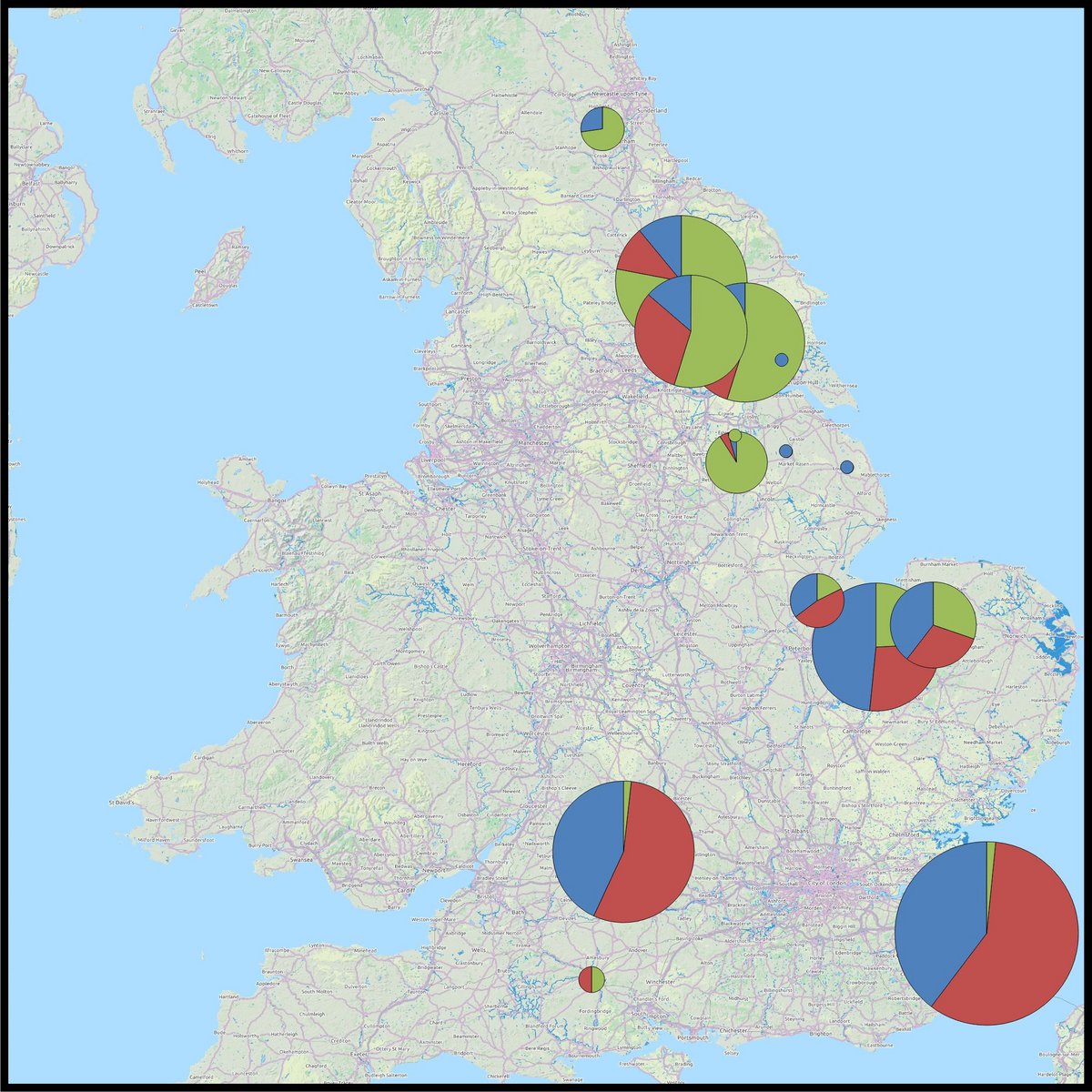

Credit: George Walkden and Donald Alasdair Morrison (Source: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/stap-2017-0007, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

George Walkden, Professor of English Linguistics and General Linguistics at the University of Konstanz, has been awarded an ERC Starting Grant by the European Research Council. His project is about what happens when different languages come into contact with one another and how this may prompt changes to the grammar and syntax of those languages.

George Walkden wants to learn more about how languages change once they come into contact with each other. He is specifically interested in what happens to the grammar and the way phrases and sentences are structured. To answer these and a range of related questions, he has been awarded a prestigious ERC Starting Grant worth approx. EUR 1.5 million by the European Research Council (ERC) as part of the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation, Horizon 2020. George Walkden was educated at the University of Cambridge and has been Professor of English Linguistics and General Linguistics at the University of Konstanz’s Department of Linguistics since 2017. His main research interests are in historical linguistics and language change, especially morphosyntactic change, with a particular focus on the Germanic languages.

“The ERC Starting Grant puts me in a position to study language change from a very broad perspective”, Walkden explains. “The basic idea is to look at how different kinds of language contact situations affect the syntax of the languages involved over their histories. In recent years, there has been quite a lot of interest in how language contact affects the structure of language, in particular the morphology – that is the structure and shape – of individual words, but there has been relatively little work on syntax specifically. That’s where my project comes in. The overall aim is to bring in as many languages as I can to test the theory, including languages from outside Europe”.

His theory about language change is based on the observation that individuals who learn a second language tend to make “mistakes” simply because learning a second language is hard as compared to acquiring language as a baby. Not only does Walkden want to understand what it is precisely that makes them difficult. He is also and more specifically interested in the long-term effects: “For instance, if you have a population of people where a lot of them have learned the same language as a second language, you might expect some of the ‘mistakes’ they are bound to make to make their way into the grammar of the language in general. Second-language learners of German, for example, might not get case endings right. The theory is that if there are enough people who learn a language who are like that, it’s probably going to affect usage on a wider level”.

As Walkden explains, syntax can be viewed as putting together words or units into clauses or sentences. The mechanisms that people use to put these words together are believed to be more or less innate in that they are part of what being human is. “However, the individual items that are put together are not innate, they are something that all of us have to learn”, he says. These items are made up of syntactic features that determine how sentences are put together. These features can either be meaningful or meaningless, i.e. they can be interpretable or uninterpretable (in the terms used in generative syntactic theory). “A classic example of a feature that is semantically not interpretable is gender in German. There is nothing particularly neuter about the German word for eye (‘das Auge’, with a neuter article) when compared to the German word for nose (‘die Nase’, with a female article). In this case, the gender feature is not interpretable”.

Research has suggested that it is these uninterpretable features that are vulnerable when second-language learners start learning a language. Walkden’s hypothesis is that, in fact, they may disappear entirely over time when large numbers of second-language learners are involved. This is something that researchers believe may have happened to the English language, which was learned extensively as a second language by Celts and Vikings during the medieval period. “This is actually what got me started on this topic”, says Walkden. “The question that I kept coming back to in my previous research on individual changes that have happened in the history of Germanic is this: ‘Why is English different from the other Germanic languages?’” Like German, Dutch and Icelandic, English is descended from Proto-Germanic. But it is very different to those languages: “It has many French and Latin words, amongst others, but that’s not all. The grammar and the structure are both very different and the morphology is virtually non-existent. I wanted to know how this came about”.

George Walkden believes that there are deeper patterns at work here that are worth looking for: “Since Chomsky’s early work on syntax, a large part of syntactic structure has often been thought to be innate to humans. Partly because of this, the idea of positing a link between particular types of language structurally and the historical context in which they emerge has not been very widespread in recent linguistics. There is a lot of evidence to suggest that the innateness assumption is correct. My question is about those parts of syntax that are not innate, that are learned. I’m intrigued to find out whether we can identify patterns for language change there”.

Facts:

- ERC Starting Grant for George Walkden, Professor of English Linguistics and General Linguistics at the University of Konstanz’s Department of Linguistics

- Project on language change prompted by different languages coming into contact with one another as well as on the long-term effects that language contact may have on the syntax and grammar of the languages involved

- Funded by the European Research Council (ERC) as part of the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation, Horizon 2020

- Funding amount: approx. EUR 1.5 million

- Funding period: five years